You’ve surely heard the protest chant:

“What do we want?

“[Insert social change here.]”

“When do we want it?”

“NOW!”

But imagine walking by a protest and hearing this:

“What do we want?”

“We’re not really sure!”

“When do we want it?”

“Whenever you get around to it is fine! Thank you!”

Doesn’t have the same ring to it.

And yet that’s closer to how we talk to ourselves when we’re trying to make a change to our habits or routines. We say to others, “Do it or else,” but we say to ourselves, “Give it a try sometime…or not. Do whatever you feel like!” Through my research for my book Indistractable, I’ve found that by understanding what facilitates social change, we can finally inspire personal change. Here are three lessons.

Precommit to change

A pact is a precommitment to an outcome that acts as a firewall against distraction. You can think of it as a sort of “habit bet.”

This technique nearly guarantees you’ll follow through on any commitment you choose to make. As I wrote about in my book, I made a “burn or burn” pact to finally get myself to start exercising regularly. My precommitment: I would either burn some calories by exercising daily or burn a $100 bill. Today, at 43, I’m in the best shape of my life.

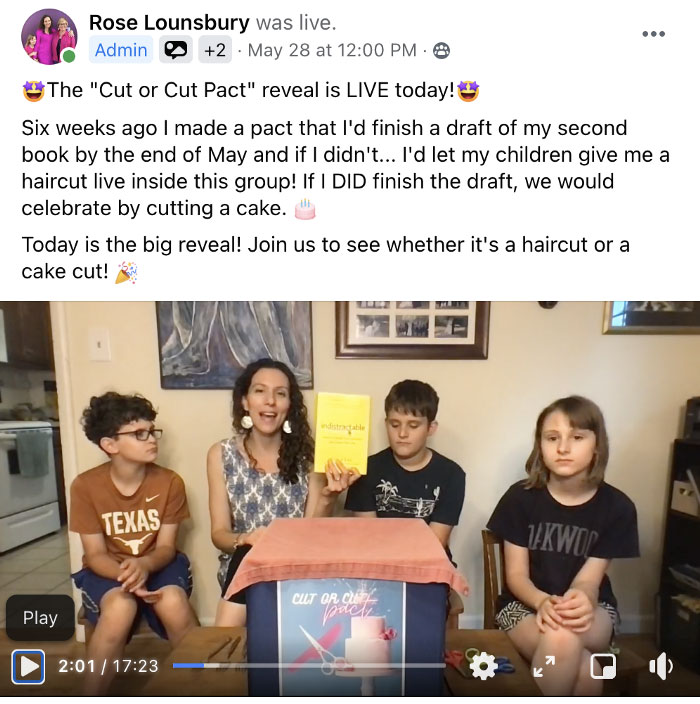

Inspired by my story, Rose made what she dubbed the “cut or cut” pact. Here’s how it worked: If Rose finished her manuscript by her self-determined deadline, she would get to cut into a celebratory cake. But if she didn’t, she would let her kids cut off her long, curly hair.

Last month, her three kids sat in front of a box that hid either cake or scissors inside. Can you guess what happened?

Revealing the results of her “cut or cut” pact, Rose Lounsbury shares what she learned reading Indistractable.

Why pacts work

Like a good protest slogan, a good pact demands action. Personal change, like social change, is hard and uncomfortable. When other tactics aren’t enough, you need to agitate the status quo.

A pact, like a protest slogan, is urgent, specific, and has a serious and unavoidable consequence.

Follow this format of a good protest slogan to make a good pact.

What do you want?

The best pacts are based on concrete behavior, not aspirations. Don’t set a vague goal like “live healthfully,” “save money,” or “spend more time with my family.” Name a very specific behavior you expect yourself to do.

When I made my “burn or burn” pact to exercise daily, I committed to exercising every day, just as Rose committed to writing her manuscript.

When do you want it?

Just having a behavior in mind isn’t enough. After getting clear on what specific action you will take, you must make sure you put that time into your schedule.

For instance, to make sure I didn’t have to burn the $100 bill, I booked time in my day for exercise. Deciding in advance when you will do what you say you will is called setting an implementation intention, and studies have found that it’s a critical step in accomplishing your goals. To do what you want, you must set aside the time now.

Or else?

The most important part of a pact is the consequence of inaction. A precommitment acts as a firewall against distraction by imposing a cost to going off track. It’s the fear of not doing what you say, which provides the extra motivation to follow through.

In my case, it was the lost cash. In Rose’s case, it was her lost hair. The potential cost must hurt or it won’t prove effective.

While making a pact can be incredibly effective, it’s important to note that pacts aren’t good for every goal and must be done after implementing the first three steps to becoming indistractable. Pacts can backfire if you haven’t mastered internal triggers, made time for traction by scheduling your day, and hacked back external triggers. When Rose made her “cut or cut” pact, she had already done all that.

It’s also important to ensure you’re working toward the right goals. If you commit to taking the wrong steps with a pact, you’ll do them, but they might not get you what you want. For instance, if you make a pact to run every day because you want to become more fit, but you don’t also watch what you eat, you won’t make progress toward your ultimate goal.

Finally, pacts aren’t great for long-term behaviors. They’re best saved for temporary goals you can commit to and achieve. For long-term behavior change, it’s better to learn to enjoy the behavior for its own sake over time. I call this finding your MEA: minimum enjoyable action.

My “burn or burn” pact was great at getting me started, but now I enjoy exercise and actually look forward to doing it. That’s the great thing about making pacts—once they’ve served their purpose, you can let them go.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Habit Tracker Template in Google Sheets

- The Ultimate Core Values List: Your Guide to Personal Growth

- Timeboxing: Why It Works and How to Get Started in 2025

- An Illustrated Guide to the 4 Types of Liars

- Hyperbolic Discounting: Why You Make Terrible Life Choices

- Happiness Hack: This One Ritual Made Me Much Happier