Nir’s Note: This guest post is by Siri Helle, a clinical psychologist living in Sweden.

Which of the following is true?

- Screen time is the leading cause of anxiety and depression amongst teenagers

- Studies have found that screen time shrinks people’s attention span to less than that of a goldfish

- Studies show screen time causes addiction

- None of the above

The correct answer: D.

According to recent studies, overall screen time has the same negative impact on teen mental wellbeing as wearing glasses.

That goldfish study? It doesn’t even exist!

And as for the studies that “screen time causes addiction,” read on to see why that notion is bunk too.

When it comes to technology addiction, there are plenty of myths and exaggerations spread by journalists unable (or unwilling) to interpret scientific studies correctly. Sometimes bad science journalism occurs when writers stretch the studies to boost the likelihood people will click and share their articles. After all, news outlets are in the same business as the social media networks they rail against. They sell your attention to advertisers; more clicks means more revenue and sensational stories sell.

As a trained psychologist and researcher specializing in digital wellbeing, I often cringe at the gap between scientific results and the media’s account of them.

What are the Ways the Media is Misrepresenting Technology Addiction?

To help you understand what’s really going on, here are four of the most common mistakes journalists make when reporting on the science of screen time and technology addiction. Once you start noticing these errors, you will gain a useful filter for distinguishing insights versus clickbait.

1. Confusing Correlation with Causation

In 2017, USA Today published an article with the headline ”Screen time increases teen depression, thoughts of suicide, research suggests.” This is a bold claim and is based on correlational data, or a method of describing the relationship between two or more variables.

The vast majority (95 percent) of studies about mobile phones and mental health are correlational studies, where researchers compare users’ device use with a self-reported measure of stress, anxiety, or sleep at a specific point in time. Correlational studies are a useful way to discover connections that might be investigated further but say little about whether one factor causes the other. Based on the study USA Today cited, claiming screen time increases anything is an example of stretching the truth to make a more compelling headline.

It may be tempting to conclude that screen time causes depression when a study shows that depressed people tend to spend more time watching screens. However, the relationship may also work the other way around—people who are already depressed tend to spend more time soothing themselves with screens.

As a news consumer, watch out for terms like “linked to,” “associated with,” and “increases,” as they may be signs of correlational findings interpreted as causal.

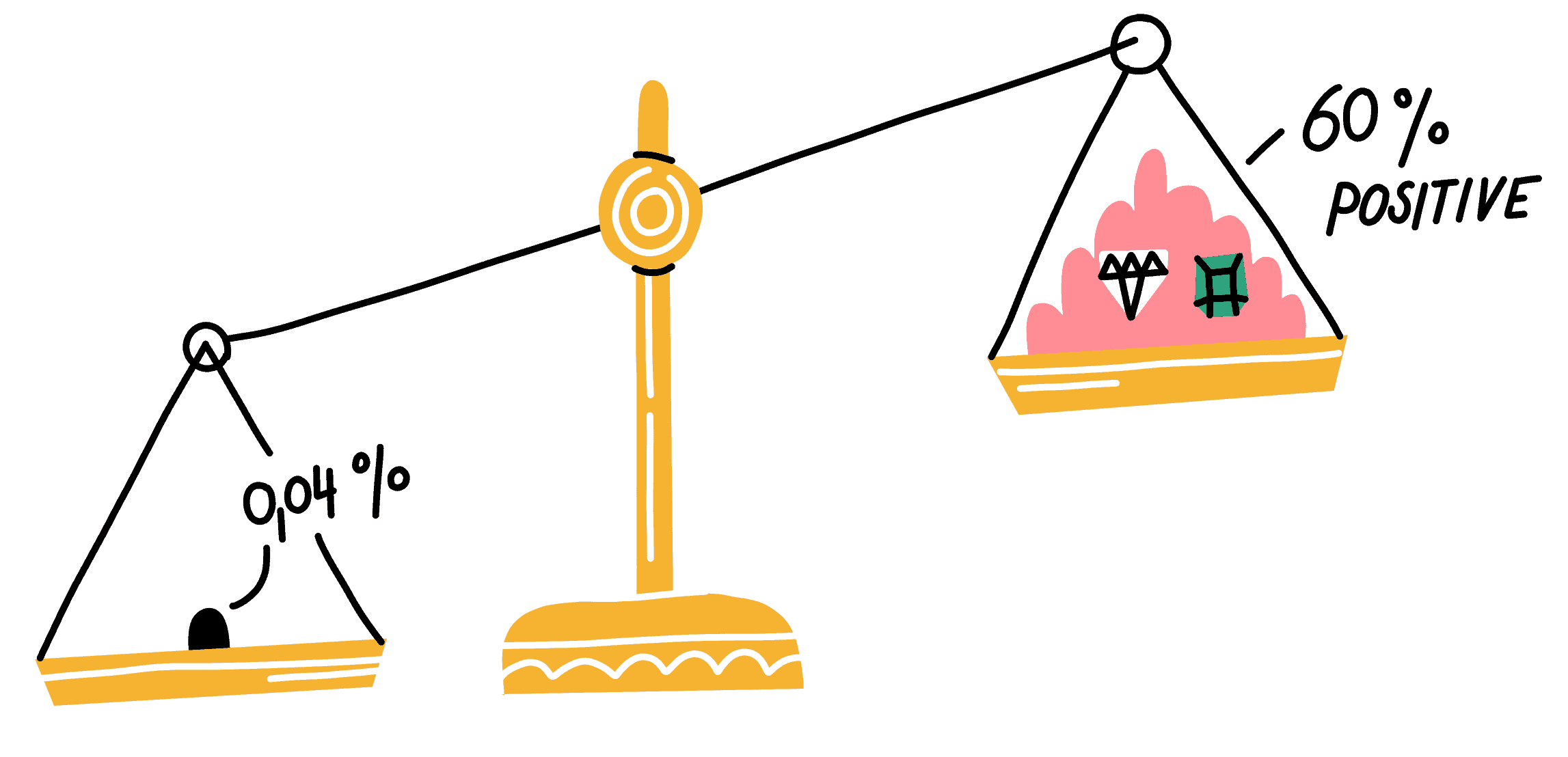

2. Not Understanding Effect Size

“Study shows social media may harm teens’ mental health.” If you are a concerned parent, seeing that headline on CNN might make you want to delete all of your kids’ accounts. Before you do, consider that the reporter never mentions how big of an impact social media has. In most studies, time on social media only explains about 0.4 % of depressive symptoms in adolescents, making it a factor of lesser importance for mental health than other relatively trivial factors, like one’s height. In comparison, having breakfast or getting enough sleep seems to have three times the effect of excessive screen time.

3. Focusing Only on the Negative

Sometimes it feels like the only things reaching the headlines are disasters, corruption, and depressing events. Why does bad news dominate the media?

In psychology, the term negativity bias describes our brains’ tendency to focus more attention on and remember bad news over good.

Technology addiction sounds alarming. Danger and fear sells, and as a result, media stories are more prone to focus on the negative aspects of technological advances.

We read a lot about how passive scrolling through social media causes envy and not as much about how interacting with people online has been shown to lighten moods and strengthen existing relationships. Media ends up feeding the negative side of the story because that’s what we tend to want to hear.

4. Medicalizing Normal Psychological Reactions

The brain works in mysterious ways, and if you’re not well-versed with how it functions, some scientific findings may sound scary. “Are teenagers replacing drugs with smartphones?” asks an article in The New York Times. It goes on to explain how phones have turned out to be “portable dopamine pumps” for the young generation.

The fact that phone use triggers dopamine releases in the brain is sometimes used as an argument that tech companies are hijacking our brains. Screens are often compared with hard drugs, and are frequently called “addictive.” The thing is, everything that makes you feel good involves dopamine. Receiving a text from your grandmother or ticking off an item on your to-do list also triggers a release of dopamine, so does having a tasty meal.

Dopamine is not cocaine in the brain. Its release is perfectly healthy and natural. And feeling excited about the next episode of your favorite Netflix series is not a case of technology addiction.

In order to develop an actual addiction, many factors need to coincide like genetic susceptibility, life stressors, and over-use of an addictive substance. There are only two screen-based activities that are known to involve addiction in this sense in a small fraction of users: online gambling and gaming disorder. If you check your phone too much from time to time, it is most likely not technology addiction, it is a distraction.

Is Technology Addiction a Real Thing?

Certainly there are many downsides to problematic screen use, many of which have been scientifically verified. For example, interruptive push notifications decrease your work performance. Passively scrolling through your social media feed might make you anxious. But overall, the effects of screens on wellbeing aren’t as bad as the media might make you think.

So, what’s the problem? Isn’t it important to inform the public about potential health risks of tech? Yes, but by exaggerating the danger of technology addiction, people might steer away from using tech in a healthier manner. The problem is that a false world-view leads to ill-formed reactions.

If you only hear about the negative effects of screens and social media, the logical solution would be to stay away from them as much as possible. But by doing so, one misses out on the opportunities provided by digital devices, like using tech to supplement connections in the real world or to learn something new online.

A popular view is that screens are like cigarettes—the less you consume the better. That simply isn’t true. A more nuanced comparison would be that screens are like food—it depends on what you’re consuming and how much.

So next time you spot a headline that warns you of the disastrous mental health effects of digital technology or how the internet might degrade your mental capacities to those of a lake-living vertebrate, remember these common journalistic fallacies. If it sounds too sensational to be true, it most likely is.

Siri Helle is a psychologist, writer, and author.

Free Distraction Tracker

Reclaim control of your attention today.

Your email address is safe. I don't do the spam thing. Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

Related Articles

- Schedule Maker: a Google Sheet to Plan Your Week

- Cancel the New York Times? Good Luck Battling “Dark Patterns”

- How to Start a Career in Behavioral Design

- A Free Course on User Behavior

- User Investment: Make Your Users Do the Work

- Variable Rewards: Want To Hook Users? Drive Them Crazy

- The Hooked Model: How to Manufacture Desire in 4 Steps